|

We met on Zoom for the first time today, November 14, 2020! Four of us are inaugural members since 2008; however, we have never met. It was so neat to SEE and HEAR each other! I recommend this for critique groups!

0 Comments

There’s something magical about turning imagination or reality into fiction—a process that’s akin to turning base lead into gold.

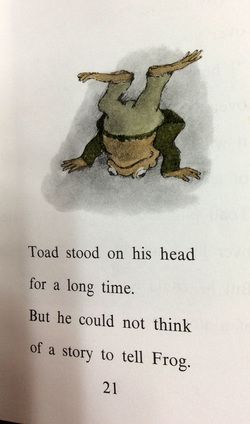

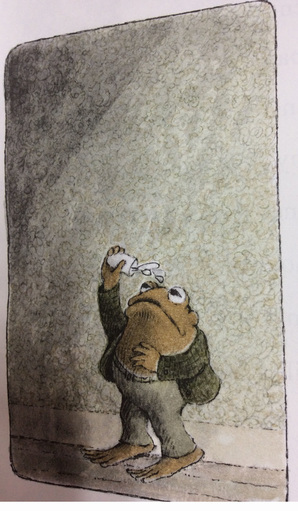

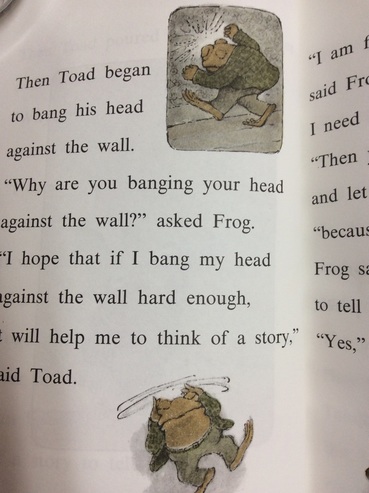

There’s no formulaic recipe for writing a story, but the ingredients that go into the stew are often the same or similar, or come from a generic garden. I would like to talk about Steven King’s ideas as he put forth in his book, ON WRITING: A MEMOIR OF THE CRAFT. King talks about having a tool box of things writers use to create stories. These are the generic ingredients which are mixed together so that no two stories are the same. The first device in the writer's tool box is vocabulary. King suggest you start with what you already have, using it to the best of your ability. As you become more widely read and more learned, your vocabulary might develop and increase. Another essential instrument is grammar. King trusts that you learned “the principles of your native language in conversation and in reading.” Or not. English classes basically teach grammatical terms though he thinks it’s important. “Bad grammar produces bad sentences.” King recommends Strunk and White’s THE ELEMENTS OF STYLE which contains basic information about punctuation, usage and misusage, and the qualities of writing that go into “style,” such as, point of view, you the writer staying in the background, and the careful choice of words. Not everyone will agree with either King’s opinions or those of Strunk and White, as writing involves very personal and individual choices. But even if your tool box is crammed full of the utensils of the writer’s craft, you also need the equivalent of the philosopher’s stone to turn your base metal into gold. It’s an elusive quality. It’s what drives writer to write; to revise and improve and to hope. King refers to that indefinable component as “magic.”  About a month ago, I introduced one of my 1st graders to Frog and Toad, who I read as a child. And lo and behold, Frog and Toad shared about finding ideas for writing a story! So while my student was reading, I was secretly thinking how to use this in a blog post! Frog wasn't feeling well and looked too green. Toad decided to tell him a story, only he couldn't think of one. So he did something about it. 1. He walked on the porch. Changing scenery and walking might help produce ideas.  2. He stood on his head. Maybe this is how you get all the good ideas to fall into your brain. ? Exercise does get the blood flowing and possibly ideas. 3. He poured water over his head. Okay, this might be a little drastic, but we understand Toad needs to be alert and quick thinking. Maybe this is the same as some of us coming up with ideas in the shower. 4. He banged his head against the wall. Don't try this one. Instead, massage your head so you're widely awake and alert. Sometimes the hair stylist massages my scalp when she's washing my hair. I found a video clip of a dad reading this chapter. Check out Frog & Toad's "The Story." Enjoy!

I'm excited to be on summer vacation with time to write. Come along with me and be proactive about finding story ideas. Just don't hurt yourself! Please share how you find ideas in the comments. In case you haven't heard, Kidlit Summer School is coming up soon. Find all the details here, plus it's free. I've done it the past two summers. A good encouraging course full of craft. Today I have the honor of interviewing Marsha Wilson Chall, the author of the new picture book, The Secret Life of Figgy Mustardo, and her editor, Jill Davis. Marsha Wilson Chall grew up an only child in Minnesota, where her father told her the best stories. The author of many picture books, including Up North at the Cabin, One Pup's Up, and Pick a Pup, Marsha teaches writing at Hamline University's MFAC program in St. Paul, Minnesota. She lives on a small farm west of Minneapolis with her husband, dog, barn cats, and books. Jill Davis has been an executive editor in children’s books at Harper Collins since 2013. A veteran of children’s books, she began her career at Random House in 1992, and worked there at Crown and Knopf Books For Young Readers until 1996, after which she worked at Viking until 2005. After that, she held positions at both Bloomsbury and FSG. She is the author of three picture books, editor of one collection of short stories, and has an MFA in Writing for Children and Young Adults from Hamline University. Mark: The Secret Life of Figgy Mustardo came about in a different way. You were asked to write a story based on illustrations of a character. Could you tell us about this process and a little about the story?

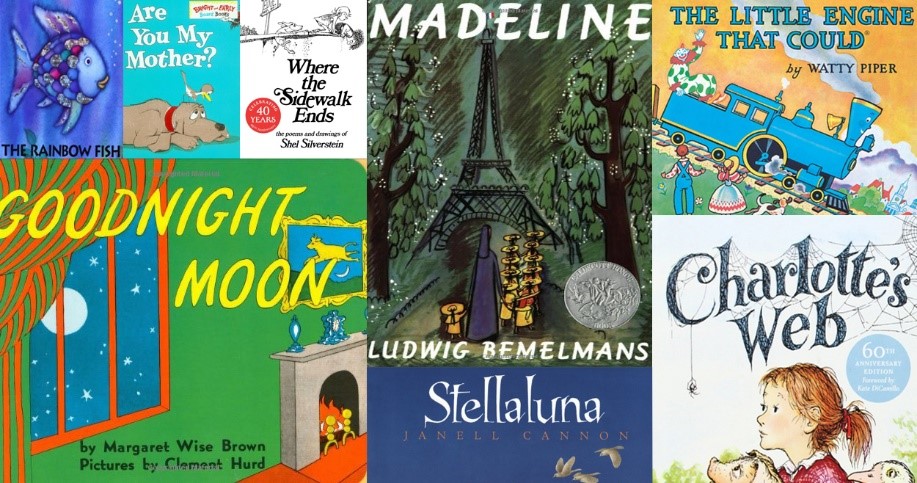

Marsha: You're right that this story evolved differently than my others. My amazing editor, Jill Davis, sent me Alison Friend's thumbnails of an adorable canine character she had named Figgy Mustardo in a variety of human-like poses and costumes. For me, it was love at first sight! So I set about the process of creating Figgy's story based on my impressions of him through Alison's art and then, via Jill, Alison's written notions of his characterization and story ideas. An imaginative, spirited fellow, Alison visualized Figgy zipping through many adventures on his scooter. In the book, I took the liberty of changing the scooter to a race car and also cast Figgy as a rock star and a pizza chef who organizes and stars in a neighborhood rock concert, pizzeria, and stock car race with his animal friends. Lots of Figgy fun, but this did not a story make. I needed to know why these activities mattered to Figgy and how he grew as a character. I also had to think about the nuts and bolts of how Figgy might transform from dog to dilettante. I was fairly certain of my own dog's boredom and loneliness while our family is away, so I started my story exploration there. We all know that dogs, as social creatures, dislike being left alone and are often fraught with anxiety leading to certain not-so-flattering behaviors and/or the escape of sleep. A story with a sleeping dog would not be too interesting, so I chose the much more exciting, destructive route. What if Figgy ate things--any things--in his frustration, fell asleep, and dreamed about himself as a manifestation of what he ate? We all know "you are what you eat," so in Figgy's case, for example, he eats Mrs. Mustardo's Bone Appetit magazine, falls asleep, and dreams of being Italian Pizza Chef Mustardo serving Muttsarello and Figaro pizzas to adoring gourmands. When he wakes, he knows his dream is a sign, so he makes a real one of his own, "Free Pizza," and serves his entire animal neighborhood at Figgy's Pizzeria. Most importantly, I needed to develop a motivation for Figgy's adventures; how were these events connected to him? What did they mean? How would they affect Figgy's world outside and inside? The answer arrived in the form of loss; every animal neighbor came to Figgy's concert and pizzeria and car race except Figgy's family, the Mustardos, especially George (his boy). In desperation, Figgy creates the sign "Free Dog" to find a family who will talk and walk and play with him like all the other families he sees through his window. Where are the Mustardos? The family Mustardo arrives in time to show Figgy how much they care with a promise to take him wherever they can and to provide him companionship when they can't in the form of new pup named Dot. Figgy and Dot go on to enliven the neighborhood with Free Shows nightly. Mark: What kind of revising/editing process did you and Jill go through? Marsha: Once I knew my character and his problem, I dashed off the story, sent it to Jill who loved it at first sight, then sat back satisfied with a good day's work. Ha! Not the way it happened, but I did write a first draft within a few days that Jill found promising. So many drafts later that I can't even recall the original, Jill exercised plenty of patience waiting for the story she and Alison hoped I could write. I know she'll protest my tribute, but I have never worked with an editor so open to my trial and error. Her abundant humor carried us through the process that I think would have otherwise overwhelmed me. Mark: Will there be any more books with Figgy and his further adventures? Marsha: Figgy hopes so and so do Jill, Alison, and I. For now, I hope Figgy wags his way into the hands and hearts of many human friends where he belongs. WOOF! Mark: How was this project different having a character first and then having to find a writer to tell his story? Jill: It was kind of hard. The illustrator had invented this little dog who she wanted to be an adventurer—yet she wasn’t sure how to make the story happen. When I saw the dog, I thought of Marsha’s One Pup’s Up—and I knew how talented she was. Seemed like a slam dunk! But all of us—Marsha, myself, and the illustrator, Alison Friend had to share plenty of feedback, edit, and revise a bit before Marsha was able to tell both the story she envisioned as well as the story Alison had in mind. Marsha pictured Figgy at home, and really loved the idea of using signs. Alison seemed to feel Figgy was some kind of James Bond. So how were those two visions going to meet? They finally did when Marsha realized that Figgy would go to sleep and dream about his exciting alter-ego. And we all loved the idea. The book may seem a little bit sad because Figgy is always being left at home, but Marsha told it in such a great way, that Figgy showed his grit! If he’s hungry, he eats what’s there—but then the magic happens and he goes to sleep and dreams of something related to what he ate. It’s so fun and so imaginative. I love what Marsha did with Figgy’s story, and Alison did, too. Mark: What was it like to work with Marsha in this new role as editor after being her student in the MFA in Writing for Children program at Hamline University? Jill: It felt very wonderful and natural. Marsha does not use intimidation as a tactic in general. She’s the rare combination of brilliant and super silly. That’s one reason she’s so loved at Hamline and in the continental United States, generally speaking. There were times when she should have been frustrated or wanted to spit at me, but she was cool as a cucumber in the freezer in the North Pole. So professional and what I loved also about working with her is how much I learned: a lot. I learned how she makes use of repetition, alliteration, and very careful editing. I can be sloppy, but Marsha walked straight out of Strunk and White. She’s exact and wonderfully detail oriented. She was also involved at the sketch stage. Actually at several sketch stages. We worked on the phone, we worked at Hamline, and we worked until we thought it felt perfect. And she loved it because she could use it in her teaching! And I just loved working with Marsha! Mark: Thank you, Marsha and Jill for taking the time to tell us about your collaboration on The Secret Life of Figgy Mustardo. The book is now available at your local independent book store. Hundreds of pictures books are published every year, and most years few, if any, will make it to the literary canon of The Classics. Some will not have this endorsement for years to come, and some rise to the top of “must have/must read/must own” almost as soon as they appear. If they are there for many generations, they are called “classics.” Without getting bogged down by which are the greatest, I can think of some books grandparents have read to our parents who then read them to us, and we now read to our kids. Picture books like Where the Wild Things Are, Goodnight Moon, The Snowy day, The Giving Tree, Make Way for Duckling and too many by Dr. Seuss— all qualify. The classics have a few things in common. Undeniable are these aspects found in all of them:

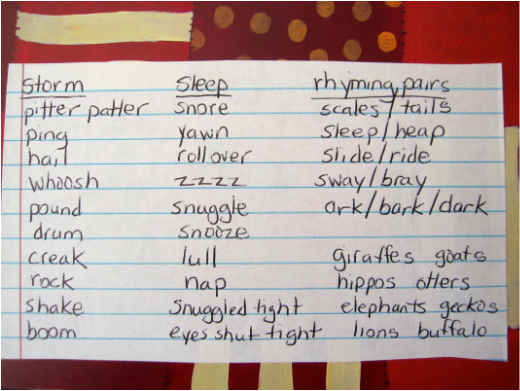

Many books do not make it past a generation. There is an element of timing and to be frank, serendipity. But although a writer can’t churn out a classic, I try to approach every story I create as if it is what I am making. It makes a stronger story.  I am a list maker and have been all my life. As a child I wrote lists of what I wanted for Christmas and birthdays. I also kept lists of the books I read. I was a proud member member of the “Newbery Award Club” – group of kids dedicated to reading every Newbery to date. My mother was a list maker too. And so was her mother. I know this because my mother insisted that I make packing lists before traveling and showed me how to do it. And my grandmother kept lists on index cards documenting every single dinner party she ever hosted, who came, what time they arrived, and what she served. I have those index cards and I’ve actually been contemplating resurrecting one of her dinner menus just for fun. But I digress. Back to lists. Now that I’m in my mid-forties, and somewhat forgetful at times, I keep daily lists to help me remember the things I need to do. I have a list of all the places I have lived. For awhile, I kept a list of every new word I learned. And I still keep lists of the books I have read and the books I want to read. This post actually is becoming a list of all the kinds of lists I like to make. The point is – I couldn’t survive without lists. Neither could my writing. Flip through any journal of mine and you will see lists. Lists of potential story ideas. Lists of potential character names. Lists of favorite memories. Lists of craft ideas and poem ideas. You name it, I’ve listed it. Indeed, lists have become one of my go-to strategies for combatting writer’s block. But even after I have an idea and the creative juices are flowing, lists play a crucial role in developing that idea. As I wrote GOODNIGHT, ARK, for instance, I paused many times to make lists. I wrote lists of fun rhyming pairs and vivid animal sounds. I made lists of cozy bedtime words and fiercesome storm words. And, as I point out to students at school visits, those lists helped immensely! Indeed, many of the words and ideas generated in those lists appear in the final version. Are you a list maker too? If not, why not give list-making a try this week as a way to get those creative juices flowing! Have fun! -Written by Laura Sassi  I recently returned from an inspiring weekend at the SCBWI Spring Spirit Conference in Citrus Heights, California. The most thrilling was my manuscript being chosen as one of the few to have a face-to-face critique with a professional in the children’s writing community. I was honored to spend this time with the delightful Alexis O’Neill. She writes picture books, most recently the multi-awarded The Kite that Bridged Two Nations. She also presented a valuable, hands-on workshop “Creating a World in 800 Words or Less.” Alexis provided a worksheet with simple tips on how to “layer” our revisions. She suggests that each time we read our story; focus on one layer at a time.[1] In other words, read it through concentrating only one aspect, perhaps verb choices. The next time, read it through concentrating only on dialogue. And so on. I slip easily over certain parts of my manuscripts and “hear what I want to hear.” I find this approach useful, to intentionally focus on one layer at each re-reading. This is also a method to try when critiquing the manuscripts of those in your writing group. You can give specific feedback, which is much more helpful for the writer than generalizations. Character: Is the main character’s desire and problem clear? Believable? Do all characters in your story belong or can you trim? Is the main character different in some way (or has consciously decided not to change) by the end of the story? POV: Is the point-of-view the best perspective? Will your story work better from another POV? Try having another character tell the story; maybe from the pet’s POV rather than the kid’s who owns the pet. Dialogue: Does your character sound his or her age? Are you making tags invisible and avoiding adverbs? Plot: A picture book has 32 pages – 14 double-page spreads. Is the story line clear? Does your story have a question that pulls the reader through to the end to find out the answer? (I love this challenge!) Vocabulary: Are you employing rich language choices? Varying sentence lengths? Limiting adjectives? Making every word count? Using strong verbs? Surprising readers with a simile or metaphor? These choices add up to what editors call “voice.” Verb Tenses: Are you using active rather than passive verbs? (The squirrel nibbled the nut rather than the nut was eaten by the squirrel.) Show Don’t Tell: Can readers “see” each scene? Do you struggle or glide passed any of these areas? Try layering. Read it aloud. Be brave and have someone else read it aloud. Listen for rough spots, slow spots, confusing spots. Revise; and then go back to focus on each layer again. Soon your story will be ready for submission day! [1] Tips taken from: Creating a World in 800 Words or Less; Picture Book Revision Tips. Alexis O’Neill. 2016 by Trine Grillo  IPop Quiz: What do you call this line (-), this line (–), and this line (—), and how do you use them? Don’t know? Me neither! I LOVE sentences. I love reading amazing sentences for the poetry and rhythm and knock out punch they can pack. I love writing sentences and the feeling of finally getting it to say exactly what I want to say and how I want to say it. To do this, punctuation is key. I think I’ve always thought of punctuation as mere mechanics though—the rules between the words. I’ve thought of them as far inferior to the words themselves. Maybe they are. But they can help those words more than I realized. Punctuation is essential for conveying nuances of dialogue and conversation, for creating emotional impact, suspense, tone, setting, etc., and for crafting a knock-out sentence. So I ask myself: HOW CAN I NOT KNOW ALL THE WAYS TO USE AN EM-DASH?! Before I answer that question, I will give you a partial answer to the quiz above. The baby one is a hyphen, the middle one is an en-dash, and the big long one is the em-dash. Don’t ask me what the first two do. One blog a time. True or False: The em dash is considered the most versatile of all the punctuation marks? TRUE! Multiple Choice: The em dash can replace what other type of punctuation in a sentence: a) commas b) parentheses c) colons d) semi-colons e) periods d) all of the above. (Hint: it’s this one!!!!!!) Em dashes are like the “O” blood type of the punctuation world. They are not interchangeable with these other punctuation marks however, so learning when and how to use them properly is key. So, now that you’re sold on this marvel of modern usage, let’s see how to do it. 1) The em dash to set of a series is the most common usage, and the one that needs the least explanation. EX: Of all the food she packed for lunch—fruit, cheese, salad, bread—she ate the cheese the fastest. 2) The em dash in place of COMMAS can make a clunky and cluttered sentence more readable. Em dashes will also place more emphasis on the sequestered words or phrase. EX: And yet, when she thought about what the cheese cost—nearly two dollars an ounce—she decided she should have savored it more, leaving her regretting the extravagant purchase. 3) The em dash in place of PARENTHESES should be used when there are multiple commas inside the parenthetical. Again, em dashes will draw more attention to the content of what’s between them so if you want the addition to be subtle, keep the parentheses. Despite them being more emphatic, em dashes are less dramatic of a break in the sentence so they will maintain flow better. (If replacing a parenthetical at the end of a sentence, just use one em dash.) EX: The next day for lunch—although she had even less time to eat, since there was a meeting at 12:30—she took tiny bites, closed her eyes, and chewed slowly. She decided the extravagance was worth it. 4) The em dash in place of a SEMI-COLON, COLON, or PERIOD functions more like a hard comma. Again, it’s less formal than a colon but draws more attention. Use it to generate strong emotion. EX: She has, however, had to adjust her grocery list to meet her budget. But she doesn't really need toilet paper—she needs cheese. Three other uses are more mechanics-y to me, so I’ll just note that em dash(es) can also be used 1) to indicate interruption of a speaker or disjointedness in speech; or 2) to replace unknown or censored letters or words. I read recently that agents and editors are impressed with highly competent sentence structure and correct use of uncommon punctuation. I think knowing how to use em dashes will help make those pesky query letters and synopses easier to write since you’ll have more tricks at your disposal to craft the perfect sentence or three. Also, if you can demonstrate a mature use of punctuation in the query letter, that might make an agent/editor sit up and take notice and more likely to move onto the actual manuscript submission. Which of course will also have a sweet em dash or two. But who cares about what agents and editors want? (Well, okay—me.) But despite that, think about what you want? Do you want to write killer sentences? I do! And the em-dash is how I’m going to do it! Wait, let’s just calm down. Chocolate is great—in moderation. A well placed swear word—in adult conversation—can be incredibly effective for comedy or to express anger. But when you’re eating a diet of only chocolate and cursing every other word, neither are going to be appreciated much by you or anyone else. Some writers argue modern writing has gotten em dash crazy. These critics think the em dash should be used only when more common punctuation fails. I guess that makes sense. You don’t just go get someone else’s blood unless you really need it. Warning headed. But I like sentence variety, exactness, and getting as much substance out of my structure as I can. I think it can only help writers to learn and master all types of punctuation marks, just in case we need or want to use them. To me, it feels like a brand new tool in my writer’s toolbox—and I can’t wait to use it. Extra Credit: How do you actually make one in a computer document? Hit the “hyphen” twice and the next time you hit the space bar or return key, it will morph into an em dash. (At least, that’s how to do it on mine!) Good luck! Dear Reader,

Let's talk about “person” in a story, that is to say, what personal pronoun shall a writer use to address her audience? If you have read much Victorian literature, you will recall that the writers often spoke directly to the reader, using the “second person.” This method is not used quite so much these days, but Kate DiCamillo, in THE TALE OF DESPEREAUX, just before the first chapter begins, says, “The world is dark, and light is precious. Come closer, dear reader. You must trust me. I am telling you a story.” Oftentimes when a writer starts a new story, several elements cohere at once. Suddenly, he has a great concept and begins to hang the premise on a particular person, place, or situation. He might be able to see the Plot from the beginning and know exactly how it will end. He can see his Main Character and knows how he looks, thinks, and feels. We want to tell our story the way we feel is most effective, so choosing which person to use is an important element for us to decide. Nowdays, most children’s literature, except for non-fiction, is told in either first or third person. I have found that it pays to be flexible. Sometimes a good critique group will be able to help by suggesting that I (or You) try re-writing the story in another person to see if it would produce a more vivid or striking result. When you do this, you have two versions of the same story to compare. You might also have to change persons for an editor or in submitting the story to a different publisher. Research is the way to get to know publishers’ and agents’ preferences. Here are some examples of Picture Books that all use Third Person: PORCUPINE’S SEEDS, by Viji K. Chary, begins: “Porcupine loved visiting Raccoon’s garden. He turned cartwheels on the soft grass, ate juicy apricots from the tree, and listened to the soothing water of the fountain.” CHRISTINA KATERINA AND THE BOX, by Patricia Lee Gauch, gets to the heart of the story right away: “Christina Katerina liked things: tin cups and old dresses, worn-out ties and empty boxes.” Here is the first paragraph in THERE’S A TURKEY AT THE DOOR, by Mirka M. G. Breen: “When the teacher said, ‘Have a nice Thanksgiving break and write a story about your Turkey Day,’ Niles’ head hung low. It was hard to write about Turkey Day without turkey.” These Middle Grade books are varied: Margot Finke, uses Third Person to tell about the aboriginal Australian boy in TACONI AND CLAUDE: DOUBLE TROUBLE: “Australia, sometime in the 1950’s. The full moon cast a cold light on Taconi’s naked body as four wizened elders pinned him on the ground close to a blazing fire. Sweat rolled off him, and his heart raced the thump, thump, thump of the feather drums: faster and faster.” {Claude is a chatty cockatoo}. These two Middle Grade books both are told in First Person. SHADOW BANDITS, by Cindy Davis, begins with dialogue: “Hey, do you smell something burning?” I asked, raising my head and sniffing, the same as Rags was doing beside me. Rags’ black nose wrinkled and his lips curled back a little.” Avi’s CRISPIN: THE CROSS OF LEAD takes place in England, A.D. 1377: “’In the midst of life comes death.’ How often did our village priest preach those words. Yet I have also heard that ‘in the midst of death comes life.’ If this be a riddle, so was my life.” Most editors prefer that Young Adult be in First Person. Here are two examples. MISTAKEN IDENTITY, by Linda Eadie, begins: “The white leather upholstery felt like slick ice against the backs of my legs as I slid into our limousine. I tugged at my skirt. It wasn’t really a skirt. It was more like a pair of baggy shorts. Whatever it was, it fought back and refused to cover my exposed thighs.” BEASTLY, by Alex Flinn. “I could feel everyone looking at me, but I was used to it. One thing my dad taught me early and often was to act like nothing moved me. When you’re special, like we were, people were bound to notice.” Occasionally, a First Person story in a Young Adult sounds almost like the narrator is talking to the reader, giving a more intimate feel to the relationship. BACK STAGE PASS, by Gabby Triana. “Day One. Let’s see how long it takes before the madness begins. Because it will, you know. It always does. The fake smiles, the wannabe friends, the can-you-get-me-backstage-passes?I just got here and already I want this to be over with.” Whatever person you choose to write your yarn in, I hope it will serve to present the story in the strongest and most understandable way. Stuck on what to write about? Try taking a vacation. Traveling to a new place opens the senses to new ideas and new stories. I’ve been inspired countless times to write a new story because of something I saw, heard, or experienced on a vacation. For example, while in Canada, I went for a hike and I came upon a river that appeared to be green. I spotted numerous animals and wildlife. This led me to write a counting book about various animals ALONG THE GREEN RIVER. On this same vacation, I kept hearing a pounding sound from the room next door at our resort. It literally sounded like a child was throwing a ball against the wall. This inspired me to write a story entitled, DON’T HIT THE BALL AGAINST THE WALL. It’s the story about a young boy who can’t find a place to throw his ball.  On a recent spring break vacation to Mexico, I saw a parrot in a cage at our resort. I got an idea to write a story about a parrot who wants to leave his quiet pet shop for adventure and excitement. Thus my first draft of FREDDY PARROT was written. Can’t afford to travel? Don’t have the time? You can also substitute a faraway vacation by going to a local park, a zoo, a lake, or a walk in your neighborhood. You don’t have to go far from home to be inspired to write a new story. New locations, new sights, new smells, and new sounds are all around us and right outside our doors. We can be inspired to create new stories based on things all around us. For example, last summer I drove to Minneapolis, only a few miles from my house. First I wandered around Linden Hills, a charming, quaint neighborhood with shops, cafes and an ice cream shop. I bought some ice cream and took it to a nearby park with a rose garden. I found a bench by a fountain that reminded me of the many I had seen in Europe. As I ate my ice cream, looking over the beautifully landscape gardens I felt relaxed. After I finished my ice cream, I pulled out my yellow legal pad and jotted down a draft about how to eat an ice cream cone. This later became HOW TO TEACH YOUR HIPPO TO EAT ICE CREAM. So if you are out of story ideas, try taking a vacation. You might just come back with an idea or a draft of a new story. Bon Voyage!

Posted by Mark Ceilley |

AuthorsMirka Breen Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed